SCEEUS Report No. 1 2026

Executive summary

- Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has been followed by a marked increase in political persecution. As of 29 December 2025, there were at least 4,884 political prisoners in Russia and the occupied Ukrainian territories. The actual number is probably much higher.

- Three broad and somewhat overlapping categories of victims of persecution can be identified: politically motivated prosecutions in Russia, people persecuted on religious grounds and people living in the occupied areas of Ukraine.

- The mass suppression of human rights in Russia paved the way for the war of aggression against Ukraine. It has been exacerbated by the war of aggression, which has extended political persecution to the occupied areas of Ukraine.

- The hardening of Russia’s political climate has created more favourable conditions for a foreign policy based on coercion, threats and military aggression. While it has reinforced regime stability, at least in the short to medium term, it has also made top-level decision-making more unpredictable and erratic.

An overview

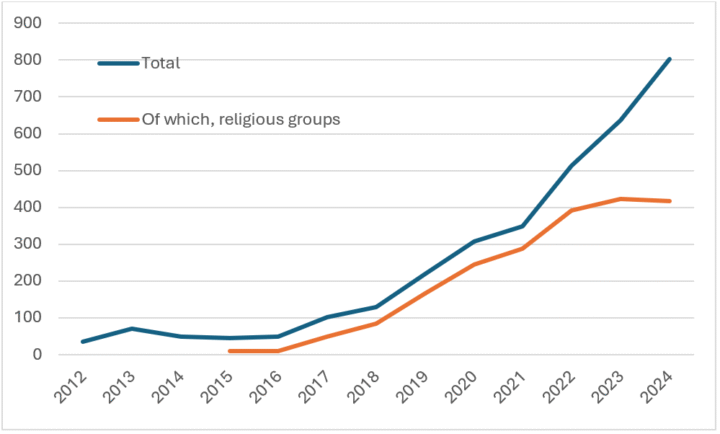

Since 2012, when the human rights organization Memorial documented 35 cases of people imprisoned on political grounds, the Russian authorities have been given a more varied legal toolbox. Figure 1 shows the increasing annual trend for political imprisonments, rising from 49 political sentences handed out by the Russian courts in 2014 to 804 in 2014. As of 29 December 2025, there were at least 4,884 political prisoners in Russia and the occupied Ukrainian territories. According to Memorial, the actual number ‘could be at least twice as high’.[1]

The main aim of the political repression is to maintain regime stability. The regime specifically targets those groups deemed most threatening, such as political activists, independent news reporting and civil society, while at the same time creating the conditions for the undisturbed recruitment of soldiers and maintenance of regional power dynamics. Repression is geographically varied and often arbitrary, which creates a high degree of uncertainty and self-censorship.[2]

Figure 1. Annual number of political convictions in Russia and the occupied areas of Ukraine

Source: Memorial, see footnote 1.

In Russia, the conventional constitutional barriers to or guardrails against abuse of power do not exist. According to Andrei Klishas, a Russian senator and head of the Federation Council’s Committee on Constitutional Legislation, the words of President Vladimir Putin ‘are stronger than the law’, and carry the highest ‘political legitimacy’.[3] Since 2022, politically driven repression in Russia has been deeply intertwined with the war in Ukraine. It stems from the authorities’ push to establish a far greater degree of societal control than previously possible, as well as a tightening of domestic policy that has unfolded alongside the war.

People with Ukrainian citizenship being prosecuted in the occupied areas constitute a large share of all court cases – about 1,200 (27 %) of the confirmed total number of cases.[4] There is a certain overlap with the persecution of religious minorities, such as Ukrainian evangelicals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Ukrainian Orthodox Christians, Catholics and people who attend weekly service in occupied territories but are not members of the Moscow Patriarchate. The number of such cases per capita is more than 3.5 times higher in Crimea and Sevastopol than in Russia. In other regions of Russia-occupied Ukraine (the “DPR”, “LPR”, and the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions), this figure is more than seven times higher.[5]

Any analysis based on confirmed court cases cannot capture the extent of the human rights situation, particularly with regard to the situation in the occupied areas of Ukraine. According to the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties, about 16,000 people have been deprived of their liberty there since the start of the full-scale invasion. Among these, some are Ukrainian prisoners of war, captured as enemy combatants. At least 410 Ukrainian prisoners of war have been put on trial in accordance with “terrorism” and “treason” statutes (see below). For example, the charge of participating in a “terrorist organization” has appeared in accusations of collaboration with Ukrainian military units designated terrorists by the Russian courts, a charge which can be combined with an accusation of treason.[6] Other Ukrainian civilians are often earmarked for deportation but remain in detention for indefinite periods.[7] Data based on court cases should therefore be treated with caution.

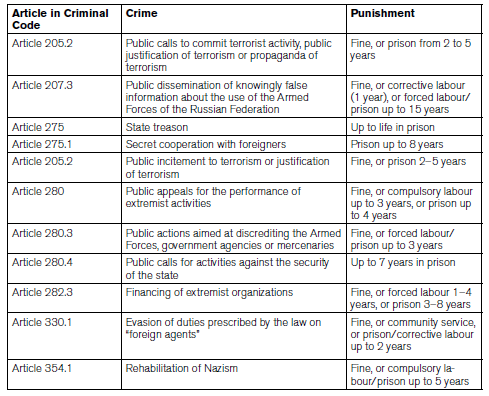

Key legal statutes

In Russia, a significant proportion of all political prisoners are people prosecuted for their anti-war stance or alleged support for Ukraine’s defence against Russian aggression. Article 207.3 (“public dissemination of knowingly false information about the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”) and Article 280.3 (“public actions aimed at discrediting the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”) are widely used in this regard. Both laws were added to Russia’s Criminal Code shortly after the full-scale invasion in 2022. Table 1 summarizes the most used legal statutes and their penalties.

Article 205.2 on “public calls to commit terrorist activity, public justification of terrorism or propaganda of terrorism” has been used to prosecute anti-war, pro-Ukrainian and pro-opposition statements. It deems illegal any statements that mention – in any way other than in the form of clear condemnation – organizations or events labelled terrorist by the Russian authorities. For example, the law was used against a political scientist who was sentenced to five years in prison for his statement that the attack on the Crimean Bridge by the Ukrainian Armed Forces was ‘expected’.

Other key articles in the Criminal Code are Article 275 (state treason), Article 205 (terrorism) and Article 275.1 (“confidential cooperation” with foreigners). According to Perviy Otdel, a human rights organization, the Russian courts (including the courts in the occupied territories) handed out 224 judgments in accordance with these three statues in the first six months of 2025. For comparison, 167 people were convicted of these charges in 2023 and 143 in the first half of 2024. In 2025, treason emerged as the most frequently applied charge in politically motivated repression.[8]

An act of terrorism has been defined very broadly, and imaginary organizations such as the “international LGBT movement” have been designated extremist. Similarly, support for Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation has been deemed by the courts as tantamount to financing “extremist activities” since 2023.

Article 275 defines treason in broad terms. It criminalizes not only acts such as espionage or the sharing of state secrets with a foreign state, but also any behaviour considered detrimental to the “security of the Russian Federation”, such as providing “financial support”, “advice” or “assistance” to a foreign state, any “international or foreign organization, or their representatives”. Life imprisonment was introduced as an option under Article 275 in 2023. A similar provision is found in Article 280.4 on “Public calls for activities against the security of the state”, which combines common threats to state security, such as the smuggling of technologies that can be used in the manufacture of weapons, with participation in organizations classified as undesirable. In this way, any interaction with foreign entities, such as NGOs, research institutes or think tanks, can be considered a crime against the state.

Table 1. Key legal statutes

Blurred lines

In addition to the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, there is also a Code of Administrative Offences, several provisions of which can be used for political persecution. The most important is Article 20.3.3, which prohibits statements or actions that “discredit the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”. Between 24 February 2022 and 24 July 2025, 11,591 people were sentenced under this provision.[9] Since the anti-war protest movement has been silenced and targeted by more repressive measures, the bulk of these were handed out in 2022 (5,511 cases). Nonetheless, the number was still relatively high in 2023 and 2024, at 2,949 and 2,119 court cases, respectively.

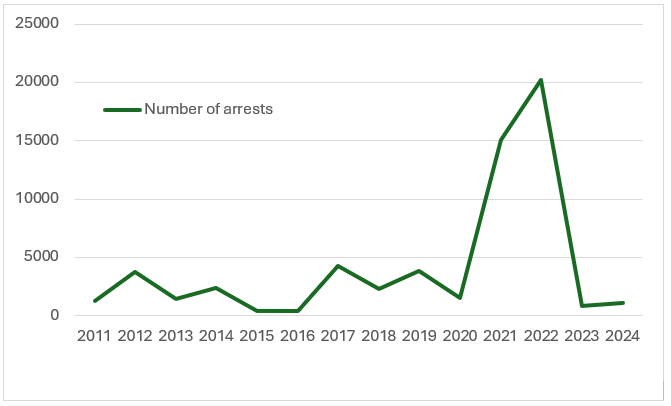

An important aim of repression is to deter individuals or groups from protesting against the state or government. It is within this political logic that the number of arrests for political reasons, including cases where no charges were brought, has increased significantly in the past five years. In 2020–2024, the Russian police made 40,595 arrests at public events such as pickets, rallies or protest marches against the war, or demanding enhanced anti-corruption measures, pension reform or constitutional reform. Figure 2 shows that the number of arrests for political reasons began to increase in 2021 (15,094 arrests) and 2022 (20,208 arrests), after which the numbers fell in 2023 (818 arrests) and 2024 (1,101 arrests). Although not all arrests are followed by charges, individuals subject to repeated arrest carry a higher risk of political prosecution.

Figure 2. Annual number of arrests at political protests

Source: OVD-Info, see footnote 8.

Some laws appear in the Criminal Code as well as the Code of Administrative Offences. For example, March 2022 amendments prohibit the spread of “knowingly false information” about the Russian Armed Forces (Article 207.3) and “calls for sanctions” against Russia, its citizens or legal entities (Article 284.2). The Russian Code of Administrative Offences introduces administrative liability for “public actions aimed at discrediting the use of the Russian Armed Forces” (Article 20.3.3) and “public pleas or calls on foreign states and organizations to impose sanctions on Russia, its citizens or legal entities” (Article 20.3.4). Typically, a first offence may lead to an administrative penalty, whereas a repeat offence within a year entails a criminal penalty.[10]

In other words, there is a blurred line between the criminal and administrative law, and it is not always obvious which will be applied in a particular case. The March 2022 amendments provide for fines of up to five million roubles and prison terms of up to 15 years for those convicted of disseminating “fake news” or any information that the Russian authorities deem to be false, notably in relation to the Russo-Ukrainian war. For example, criminal cases were opened for such allegedly inaccurate comments about the murder of Bucha residents and the destruction of Mariupol, two war crimes of which Russia has been accused. In combination with mass arrests for political reasons, the Russian authorities have made protest activities and public dissent fraught with high levels of personal risk.

Conclusions

- Political persecution has created a climate of fear and self-censorship in Russia and in the occupied territories of Ukraine. Current trends indicate that more draconian legislation is likely to be introduced.

- Enforcement of Russia’s repressive legislation varies geographically, and is arbitrary and selective. People in the occupied territories of Ukraine are particularly vulnerable. An end to the Russo-Ukrainian war on Moscow’s terms will make accountability for war crimes and political persecution in these areas impossible.

- The hardening of Russia’s political climate creates more favourable conditions for a foreign policy based on coercion, threats and military aggression. While it reinforces regime stability, at least in the short to medium term, it also makes top-level decision-making more unpredictable and erratic.

[1] Memorial, “Baza dannykh”, 29 December 2025, <https://memopzk.org/news/baza-dannyh-proekta-podderzhka-politzaklyuchyonnyh-memorial/>.

[2] Furthermore, relevant details of court cases are often kept secret. In certain instances, courts do not publish the names of those convicted of politically motivated crimes. In the occupied areas of Ukraine, there have been several instances where people were abducted by the Russian authorities, and only much later charged with a crime. Here, our knowledge about the scale of political persecution is much more limited.

[3] Vedomosti, “Slova prezidenta”, 8 December 2022, <https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/characters/2022/12/08/954257-slova-prezidenta-silnee-ukaza?from=copy_text>.

[4] Memorial Database, available at: <https://airtable.com/appvNc945GeBZzbVI/shr3YiaVWxkRrYuhe/tblgvypyXZg1UKtYf>.

[5] Memorial, “Barometer repressii”, 3 October 2025, <https://memopzk.org/analytics/barometr-repressij-iii-kvartal-2025-goda/>.

[6] Memorial, “Bolee 4000 chelovek”, 3 September 2025, <https://memopzk.org/news/bolee-4000-tysyach-chelovek-lisheny-svobody-v-rossii-s-yavnymi-priznakami-politicheskoj-motivaczii/>.

[7] Anna Snegirova, ”Thousands of Ukrainian civilians held without trial by Russia”, 7 October 2025,

<https://platformraam.nl/artikelen/2908-thousands-of-ukrainian-civilians-held-without-trial-by-russia>.

[8] Perviy Otdel’, “Kazhiy rabochiy den’”, 24 September 2025, <https://dept.one/story/gosizmena-jan-jun-2025/>

[9] OVD-Info, “Presledovanie za antivoennye vzglyady”, <https://antiwar.ovd.info/?utm_source=google.com&utm_medium=organic&utm_term=%28not+set%29>.

[10] Zona-Media, ”V rossiyskie sudy”, 21 December 2022, <https://zona.media/news/2022/12/21/badarmy5500>.