SCEEUS Commentary No. 11

Executive Summary

Amid weakening US support for Ukraine and question marks over its future commitment to European security, three political imperatives are emerging for Europe: increasing the level of military support provided to Ukraine, constraining and containing Russia’s antagonistic actions and strengthening European defence. As US aid, which as of March 2025 has amounted to €114.6 billion in military assistance compared to Europe’s €137.9 billion, stalls, Europe must step up.

A mapping of the support provided reveals that some countries are prioritising investment in Europe’s defence over the defence of Ukraine, when these efforts must go hand in hand. It is imperative to remember that a weakening of Ukraine’s capabilities translates into greater risks for all of Europe. Failing to assist Ukraine now through the provision of both military and financial aid will result in higher costs for Europe’s own defence in the future. Ukraine should be viewed as a security provider for European defence and deterrence efforts and not as a security consumer.

To increase efficiency, Europe should plan more strategic aid channels for increasing investment in Ukraine’s defence industry. Clearer communication on support is also vital to emphasise the credibility of a long-term commitment. Amid decreasing US support, Europe must increase its own defence capabilities without falling short on firmly standing by Ukraine. Policymakers in Europe cannot afford to turn a blind eye to either of these imperatives, which should be understood as mutually reinforcing.

Where Does Europe Stand with Ukraine?

The most recent meeting of the Ukraine Defence Contact Group (UDCG) on 11 April 2025 resulted in ambitious promises of continued military aid from Ukraine’s European allies. The UDCG, also known as the Ramstein format, is a coalition of more than 50 countries that meets regularly to assess Ukraine’s defence needs and to coordinate assistance. The US, which had previously hosted the meetings, was represented by link by US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth. UK Defence Secretary John Healey affirmed that 2025 is the ‘critical year’ in which Europe must step up its support. The parties announced they had agreed to allocate €21 billion in support to address both immediate battlefield needs and developments through to 2027.

The pledges made in April mark a shift compared to the two previous Ramstein meetings, which – although exact numbers are missing and the agendas do not have the same scope – yielded less ambitious commitments. Meanwhile, as Europe comes to terms with a reduced US presence on the continent, several European countries are making significant investments in their own defence.

Thus, while the pledges made at the April Ramstein meeting are significant and can be interpreted as an attempt to show resolve, they must be understood in a broader context. As European states ramp-up domestic defence spending, support for Ukraine should not be sidelined.

Shifting Priorities or Converging Agendas?

A broader perspective reveals a number of challenges and inconsistencies in connection with the support provided to Ukraine. First, the details of the numbers pledged during the meeting remain unclear. Germany, for example, committed a substantial €11 billion through to 2029. However, while this appears to reflect a promising long-term vision of support, the new pledge does not signify an increase compared to the €12.62 billion worth of military aid that Germany has provided since the full-scale invasion three years ago. In contrast, the UK’s most recent pledge of £4.5 billion in 2025 constitutes half the amount they have allocated since 2022.

Various factors complicate the assessment of both the scope and the impact of the aid pledged. Headline figures in billions are not the sole indicator of how meaningful the aid is; equally crucial is how well the aid aligns with Ukraine’s needs. Timing further complicates the analysis. Some countries adopt broader, multi-year frameworks for their support, which can skew comparisons of current allocations. For instance, the Danish model, which has gained traction among European states, channels military aid through a special Ukraine Fund that ensures long-term commitments. Another example is Sweden’s most recent support package, which was made possible by moving funds from planned assistance in 2026, thereby frontloading Swedish support.

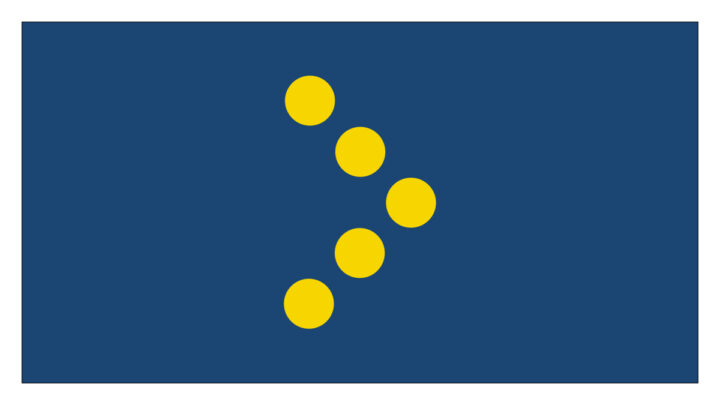

Second, there is an asymmetry among European states. Together with Poland, the Nordic and Baltic states still lead on assistance to Ukraine in relative terms. Figure 1 shows that Estonia and Denmark spend 2.3 per cent of their GDP on bilateral aid – both miliary and financial – and an additional 0.3 per cent in their share of EU aid.1 In contrast, Germany has spent 0.44 per cent of GDP on bilateral aid and France is even further down the list with 0.19 per cent allocated to bilateral aid, although it contributes more than double that in its share of EU-level aid.

Figure 1. Support to Ukraine, percentage of GDP

Source: Kiel Institute.

France and Germany are the two largest economies and leading powers in the EU, but among the lowest contributors in terms of bilateral aid as a share of GDP, alongside other major member states. Looking at support in absolute terms (see Figure 2), the level of contribution varies. It is clear that the support that France, Italy and Spain provide does not correspond to the size of their economies. In contrast, the contributions of the relatively smaller economies in the Nordic and Baltic region are significantly higher, and together amount to €25.99 billion.

Although it is not surprising that countries geographically close to Russia are more eager to support Ukraine, it can be argued that they have good reason to keep resources for their own defence. This, however, is not reflected in the data, which appears to indicate that these countries perceive Ukraine’s fight as a defence of them as well. However, as overall defence spending continues to rise across Europe, the question arises whether this will be compatible with continued support.

Figure 2. Support to Ukraine in absolute terms

Source: Kiel Institute.

Third, recent data shows that the level of European financial and military assistance provided to Ukraine has declined over the past year (see Figure 3). Europe provided €6.92 billion in support to Ukraine in January and February 2025, compared to €12.27 billion in the period January to March the previous year.2 This happened despite the widespread understanding that US support to Ukraine might stall under the Trump administration. In contrast to the support provided to Ukraine, defence expenditure in Europe has seen a drastic increase since the full-scale invasion, as is also illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Defence expenditure and support to Ukraine

Source: Kiel Institute, NATO.

Not all European countries are contributing to this sharp increase. Germany increased its defence spending from 1.64 per cent of GDP in 2023 to 2.12 per cent in 2024. Similar trends are evident in Sweden and Poland. However, the UK spent 2.33 per cent of GDP in 2024, compared to 2.30 per cent in 2023. While numbers for 2025 are not included in Figure 3, Europe is clearly signalling an objective to continue this upward trajectory in defence spending. Sweden recently announced its intention to spend 3.5 per cent of GDP on defence by 2030, which is a significant increase on the current 2.6 per cent. Poland is reportedly aiming to reach 4.7 per cent of GDP in 2025, topped by Estonia and Latvia which are aiming for 5 per cent. Meanwhile, the EU has shown a commitment to bolster European security through the ReArm Europe initiative.

While it is promising to see that Europe is taking the challenge of strengthening its own defence seriously, the decline in support for Ukraine could be interpreted as a signal that national defence budgets are being prioritised at the expense of aid to Ukraine. Figure 4 compares defence spending with support to Ukraine, highlighting that some European states might be focusing on their own defence rather than helping Ukraine, thereby further illustrating the asymmetry.

Figure 4. Defence expenditure and total bilateral aid

Source: Kiel Institute, NATO.

Conclusions

As national military expenditure drastically increases, there is a risk that the importance of continued and effective support to Ukraine might be neglected. European states must develop a shared understanding that supporting Ukraine and enhancing strategic autonomy are mutually reinforcing goals. Without decisive and substantial European support, Ukraine will be unable to withstand Russian aggression, increasing the risk for all of Europe. Overall, there is a risk that the importance of continued and substantial military and financial aid to Ukraine might be overshadowed by priorities on national defence when, in reality, the former should remain the central focus.

Three key policy recommendations for Europe therefore arise:

- European countries should explore different channels of support to encourage continued investment in Ukraine. The Danish Model is an example of how aid could be spent more effectively, as donations of military equipment to Ukraine – although valuable – are often more expensive and less efficient in the long run than investments in Ukraine’s military-industrial complex. The latter result in a more effective use of aid, as it enables Ukraine to meet its own needs while allowing key equipment to be reserved for European countries’ domestic defence purposes.

- Support should be communicated more clearly and cohesively to signal Europe’s readiness to boost its overall defence without falling short on aid to Ukraine.

- The issue cannot be reduced to a binary choice between defence spending and supporting Ukraine. As the US lowers the bar for support for Ukraine and tolerance of imperialism, Europe needs to raise it. This means not only becoming more independent in defending itself, but also standing firmly with Ukraine.

Resilience and vulnerability: Impressions from a freezing Ukraine